When the Lights Go Out

On Fragility, Dependence, and the Invisible Threads That Hold Us Together

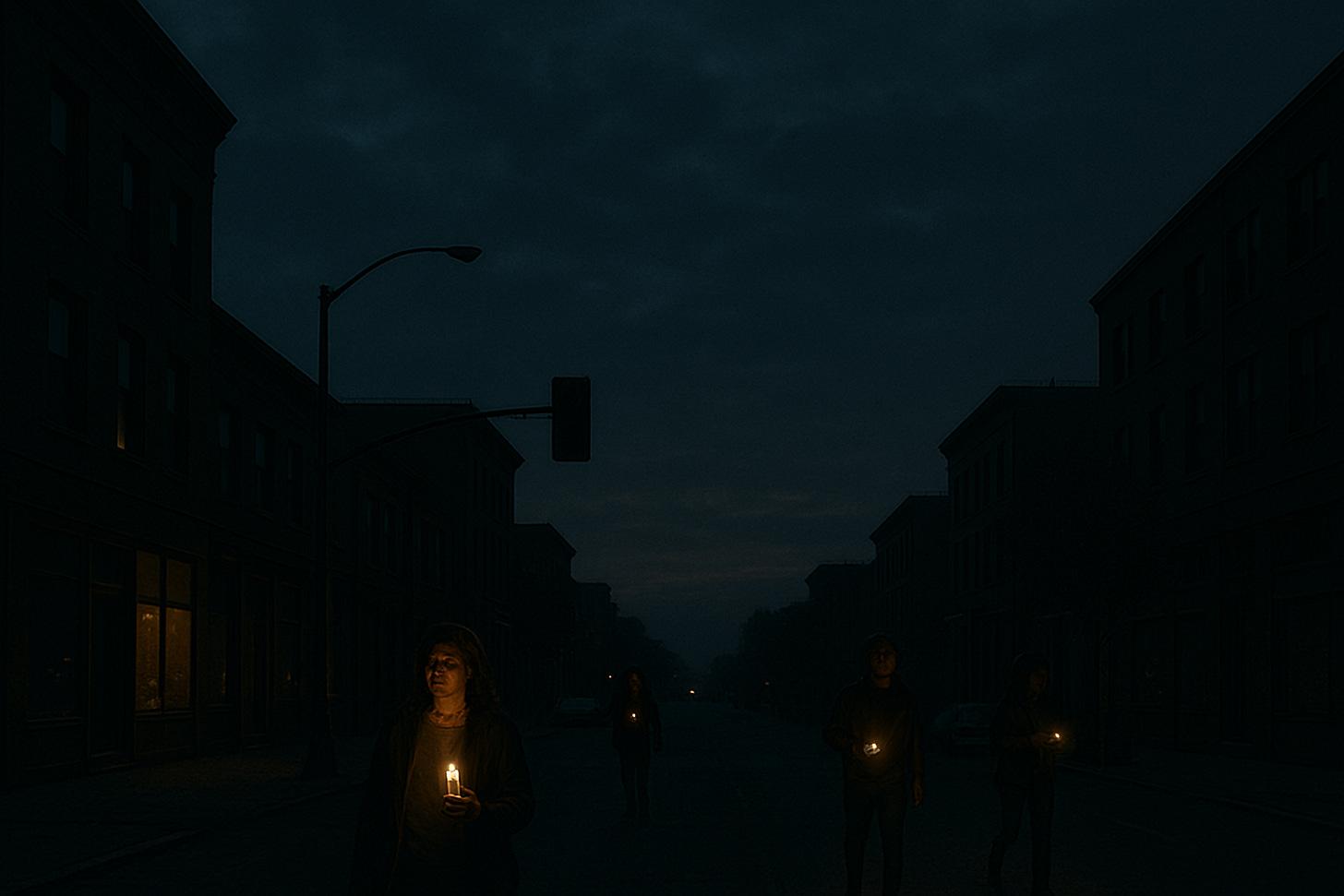

The electricity vanished as if someone had drawn a curtain. Just past noon on an otherwise ordinary Monday, vast sections of Spain and Portugal fell into sudden stillness. Trains halted, shop doors froze mid-slide, air traffic was diverted. In Madrid, street traffic crawled as signals blanked; in Lisbon, people checked their phones only to find the networks dead. Nearly 15 gigawatts of power disappeared from the Iberian grid, in a matter of seconds. The cause, at first, was unclear. No fire, no storm, no hostile actor. Just a glitch in the system — one flicker, and then absence.

There is something revealing about a blackout. It has no ideology, no declared intention. It does not persuade or protest. It simply reminds. For a few hours or days, depending on one’s location, the scaffolding of modern life becomes visible by its sudden removal. What one cannot do — call a friend, pay for groceries, heat water, keep time — grows into a kind of philosophical inventory. You learn, not through theory but through stillness, how much your daily ease depends on an invisible hum. And how fragile that hum is.

This particular blackout, which darkened the peninsula in late April, is already being dissected by engineers and policymakers. A sudden drop in solar output in southwestern Spain appears to have triggered the failure, causing the regional grid to disconnect from France. Emergency reserves were slow to respond, and the cascade spread. There was no villain, no cyberattack. Only the complex, tightly woven interdependence of a modern infrastructure system doing what it does when something vital is slightly out of place: failing.

But the story here is not, or not only, technical. It is civilisational. We live in a time when our achievements are vast but brittle. Our communications are instant but vulnerable, our transportation fast but interlinked, our comforts immense but power-dependent. The blackout serves as a kind of parable — not of decline, necessarily, but of fragility. The kind of fragility that creeps in when complexity outruns reflection.

It is striking, for instance, how easily we forget the physicality of our lives. The grid, the servers, the routers, the cables — all the unspectacular hardware that upholds the digital ether — vanish from view in daily experience. The cloud, we are told, is everywhere. But the cloud is also somewhere: a network of machines, humming and hungry, governed by rules of inertia and latency, by the limitations of storage and thermodynamics. These things obey physics, not convenience. And when they falter, the consequences are felt not in the abstract but in queues, silences, and halted movement.

The Iberian blackout, for all its disruption, was brief. Most power was restored within hours. But the deeper disturbance lingers. It is the awareness, however temporary, that we no longer quite understand the systems we depend on. The average citizen does not know what a kilowatt is, or how power moves from generation to socket. This is not a moral failing, but it is a kind of civic vulnerability. We speak fluently of rights and identity, but mutely of resilience. We assume continuity. And when it breaks, we are surprised — not because the system failed, but because we had forgotten it could.

What might it mean to take such fragility seriously, not as a reason for fear but as a reason for attention?

Not to panic, or to regress, or to romanticise some pre-electric simplicity. But to reflect on how much of our modern ideal — speed, seamlessness, automation — rests on structures that require continuous, invisible cooperation. The electricity grid is a kind of collective nervous system. It cannot be owned in any simple way, nor mastered, nor safely ignored. And the more it is driven by volatility — wind, solar, variable demand — the more it requires vigilance, not only from engineers but from citizens.

Here we come close to an ethical insight. Dependence, rightly understood, is not weakness but mutuality. The blackout teaches this not by argument but by interruption. When the lights go out, we remember how much of our agency is relational: our ability to act, to respond, to move through the world depends on others — their skills, their labour, their foresight, their maintenance. A society forgets this at its peril. And perhaps ours already has.

There is also a quieter lesson. That silence is not always absence. That when the noise stops — the electric buzz, the algorithmic feed, the digital surround — we may begin, awkwardly at first, to hear again. The hum of our own thoughts. The unmediated voice of another human being. The fact of our own bodies in space and time. These things do not vanish when the power cuts. They return. They reassert their place.

It would be too much to say that a blackout is a gift. It is not. It causes suffering, inconvenience, risk. But it can still be instructive. It can offer — if only briefly — a clearer view of what we are doing, what we are relying on, and what we are forgetting. The temptation, once the power returns, is to resume life as before, a little more grateful perhaps, but no more thoughtful. That would be a missed opportunity.

Because the question is not simply: how do we prevent the next blackout? It is: how do we live in a way that remembers we are never far from one?

Miklós Cseszneky