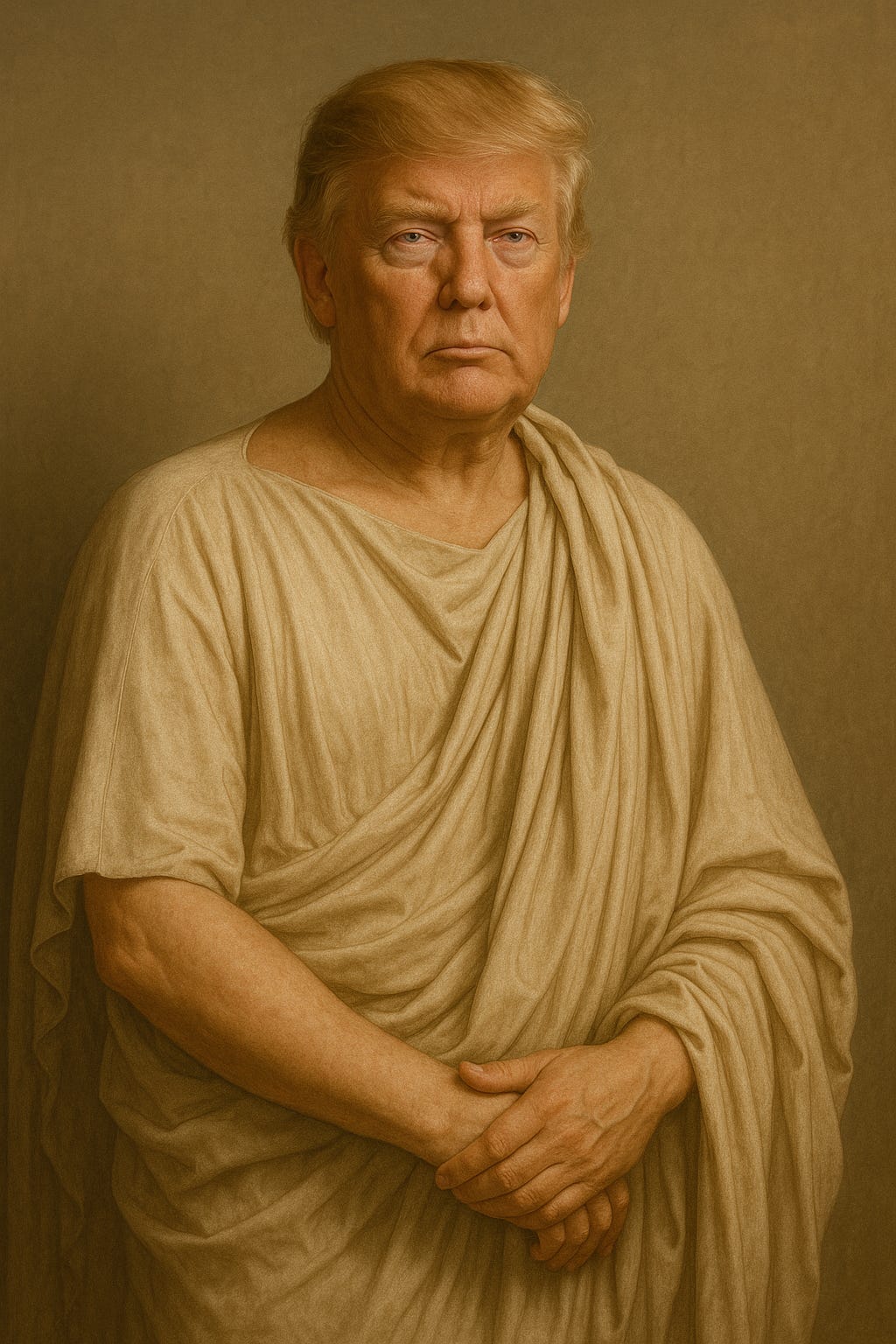

Trump, Stoicism, and the Illusion of Virtue

It wouldn’t take Epictetus long to diagnose Donald Trump.

Here is a man whose life seems driven almost entirely by externals: wealth, status, applause, insult. A man who defines himself by how loudly he can impose his desires on the world — and how stubbornly he can resist any correction.

From a Stoic point of view, Trump is a living catalogue of what not to value. Fortune, reputation, influence, domination — the very things the Stoics warned were unstable, indifferent to virtue, and ultimately enslaving if made into goals. What matters, in their view, is not what happens to us, nor how we are seen, but how we govern our minds and actions in response.

By this standard, Trump is no Stoic. He is a monument to fortune’s intoxicating noise — a case study in what happens when the inner life is abandoned to vanity and grievance.

But Stoicism teaches a discipline deeper than disapproval. Its target is not simply bad rulers or loud egos. It questions any life — public or private — built on the unstable scaffolding of appearance.

And so the real Stoic question is not, “Is Trump virtuous?”

It is: “Is anyone here behaving with philosophical seriousness?”

It is too easy to cast Trump as the villain and, by contrast, position his opponents as guardians of reason, restraint, and democratic virtue. That contrast flatters us.

But Stoicism was never concerned with flattery. It was concerned with the soul.

And when we look more closely, we see that many of those who oppose Trump fall into precisely the traps they claim to resist. The obsession with status. The demand for public validation. The theatre of moral outrage. All of it remains entangled in externals — not because their values are false, but because their posture is so often for show.

This is the real moral ambiguity of our moment.

Trump governs by impulse, tantrum, and dominance. His critics often govern by narrative, outrage, and performance. One side shouts. The other shames. But both, in different ways, are reacting — not reasoning. Both seek not just to argue, but to win. And in that pursuit, they abandon the very inner composure that Stoicism upholds.

A Stoic does not confuse anger for courage, nor public agreement for moral authority. Nor does he believe that righteous performance is a substitute for self-mastery.

Stoicism demands more:

Clarity over heat.

Constancy over fashion.

Interior strength rather than theatrical virtue.

It is easy to appear restrained when your anger wears better clothes. But too often the restraint is only stylistic. The hunger for domination reappears, just with different branding — progress rather than populism, inclusivity rather than control.

But the moral reflex remains the same: crush the other side, claim virtue, and seek applause.

Marcus Aurelius ruled an actual empire under pressures we can hardly imagine. He did not write Meditations to posture, to persuade others, or to appear virtuous. He wrote to maintain his own mind.

His private reflections — often fragile, often self-correcting — were exercises in governance of the self. Not signalling. Not rhetoric. Preparation for the hardest task: to remain human in the face of power.

We, living under far lighter burdens, have forgotten the principle. We perform our positions. We outsource our reasoning to factions. We confuse being visible with being good.

The self becomes a signalling system, not a structure to be built.

If a Stoic were watching this from a quiet corner — and perhaps they are — they would see not just a political decline, but a philosophical one. Not just disorder in governance, but disorder in soul.

They would not be scandalised by Trump.

They would expect him.

What would concern them more is that so many who oppose him have chosen to mirror his behaviour — not his policies, but his attitude: reactive, self-certain, addicted to spectacle.

Stoicism does not demand passivity. It does not forbid action or conviction. But it demands that our actions flow from principle, not from performance. And it demands that our resistance to disorder not itself become disorder — loud, unstable, and driven by fear of appearing weak.

A Stoic sees more than a battle between populist chaos and liberal morality. He sees a stage, filled with roles, and asks:

Which actors still remember they have an inner script?

Who still governs themselves before they attempt to govern the world?

We may not like the answer.

But we should be prepared to ask the question.

Because if we fight noise with more noise, we lose the very thing we claim to defend:

The quiet, difficult discipline of living with integrity.

Miklós Cseszneky