The Silence of the Board

What the Taliban's ban on chess reveals about fear, culture, and the enduring power of thought.

In April 2025, the Taliban officially banned the game of chess in Afghanistan. The announcement was terse, the reasoning familiar: it was “forbidden in Islam,” according to the regime’s spokesman, due to its supposed connection to gambling. No further justification was given, and perhaps none was thought necessary.

At first glance, this might seem like a minor edict compared with other repressions — schools closed to girls, music silenced, journalists exiled. But it is worth pausing over this particular act. Not because it is new (chess was banned during the Taliban’s first rule as well), but because of what it reveals about the nature of power, culture, and the quiet forms of human dignity that authoritarian regimes so often seek to extinguish.

Chess is not just a game. Or rather, it is a game in the oldest, most enduring sense: a ritual of thought, an emblem of patience, a theatre for strategy and restraint. It requires nothing but two minds and a board. No spectacle, no noise. Just silence, attention, and consequence. And because of that, it carries with it a kind of moral seriousness — not moralising, but moral form. One learns to think ahead. One learns to lose. One learns that even with equal pieces, outcomes vary depending on vision, care, and timing.

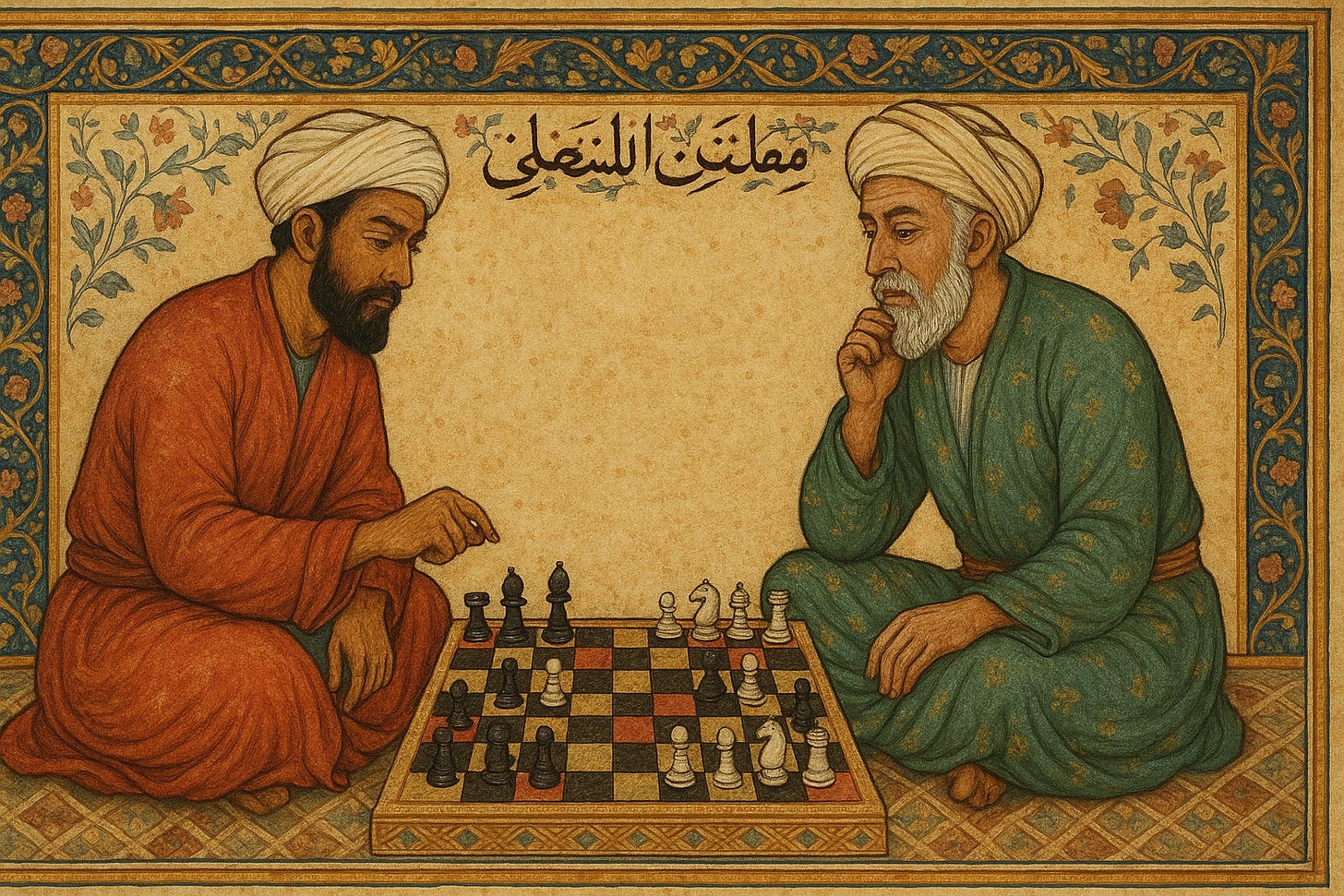

It is no accident that chess has travelled so widely across civilisations, and so deeply into them. Its origins lie in northern India in the 6th century, but it was in the Islamic world that the game flourished and developed into something recognisably close to what we know today. By the 8th century, it had spread from Persia to the Arab world, carried into the courts of the caliphs and the homes of scholars. The early Islamic thinkers saw in chess not a vice, but a mirror of life and power. Manuscripts were written on chess strategy alongside treatises on mathematics and astronomy. It was played by poets and princes, and referenced in literature from Andalusia to Baghdad. In its structure, many saw echoes of justice and governance — a world of limits, governed not by whim but by rules, where every move carried weight.

To ban chess, then, is not only to suppress a pastime. It is to sever a cultural inheritance, to erase a thread that connects Afghanistan to centuries of intellectual life within its own religious and civilisational tradition. That matters. The regime that now governs from Kabul may speak in the name of Islam, but its actions reveal a deep hostility to the historical breadth and complexity of Islamic culture itself.

The given reason — that chess is linked to gambling — is tenuous at best. There is no element of chance in chess. It is, in fact, the opposite: a realm where randomness is excluded, where the only variables are human thought and time. But perhaps that is precisely the point. Authoritarian regimes do not fear games of luck. They fear games of reason. They fear practices that encourage strategic thinking, the weighing of options, the cultivation of foresight. They fear the interior life that such games imply.

Chess trains precisely the faculties that repressive systems seek to dull: judgment, restraint, independence of thought. To sit at a chessboard is to enter into a discipline — one in which actions are not reflexive, and outcomes are earned. It fosters a kind of interior sovereignty: the knowledge that one’s decisions, not one’s slogans, shape the field.

The Taliban’s discomfort with this is unsurprising. They have already banned music, silenced dissent, dismantled most forms of artistic and intellectual life. Their vision of order is not one that accommodates ambiguity or delay. It is immediate, total, and rooted in fear. Chess, by contrast, requires ambiguity. It requires time. It asks the player to pause, reflect, consider. And, in doing so, it becomes a small rehearsal in moral patience — a concept that totalitarian ideologies find intolerable.

There is something else, too. A culture that can no longer tolerate chess is not simply afraid of subversion. It is afraid of memory. Because chess is also a symbol — a relic of a world in which Afghan, Persian, Arab, Jewish, and European minds shared more than they fought. The board is a meeting place. Its language is not tribal. Its discipline is not sectarian. There is no “us” and “them” on a chessboard. There is only black and white, in shifting roles, governed by rules that both players must follow. In a regime that governs by division and domination, that, too, is intolerable.

But such bans rarely achieve what they intend. History shows again and again that the most durable forms of resistance are often quiet: the private rehearsal of a forbidden melody, the secret reading of a banned poem, the unspoken passing of knowledge. So it is with chess. The boards will go underground. The strategies will be whispered. Parents will teach children in hushed tones. And in this quiet continuation, there is a kind of defiance — not dramatic, but durable.

There is no need to romanticise chess, or to elevate it beyond its place. It is not salvation. It does not prevent injustice. But it is, and has always been, a practice of thought within limits. And that practice — modest, non-performative, demanding — is one of the most human things we have. In defending it, we are not only defending a game. We are defending the principle that reflection matters. That the life of the mind is worth protecting. That not everything must serve a propaganda function.

And perhaps, in the end, that is what makes chess subversive in a place like Taliban-ruled Afghanistan. It serves no dogma. It teaches no slogans. It demands no loyalty. It simply asks: What will you do now? What consequences will your actions bring? Can you see more than one move ahead?

Questions like these, quietly asked, can be more unsettling to tyrants than any demonstration. Because they awaken something regimes cannot command: the capacity for judgment. And when that is gone — or forbidden — what remains is not obedience, but hollow imitation. A society without thought. A life without perspective.

To those who keep playing — even if only in memory, in secret, or in hope — the world owes a kind of reverence. Not because they are revolutionaries, but because they are preserving a form of life that says: rules can be learned. Mistakes can be corrected. Time, space, and consequence matter. And dignity — even on a board of 64 squares — can still be quietly affirmed.

Miklós Cseszneky