The Authentic Man

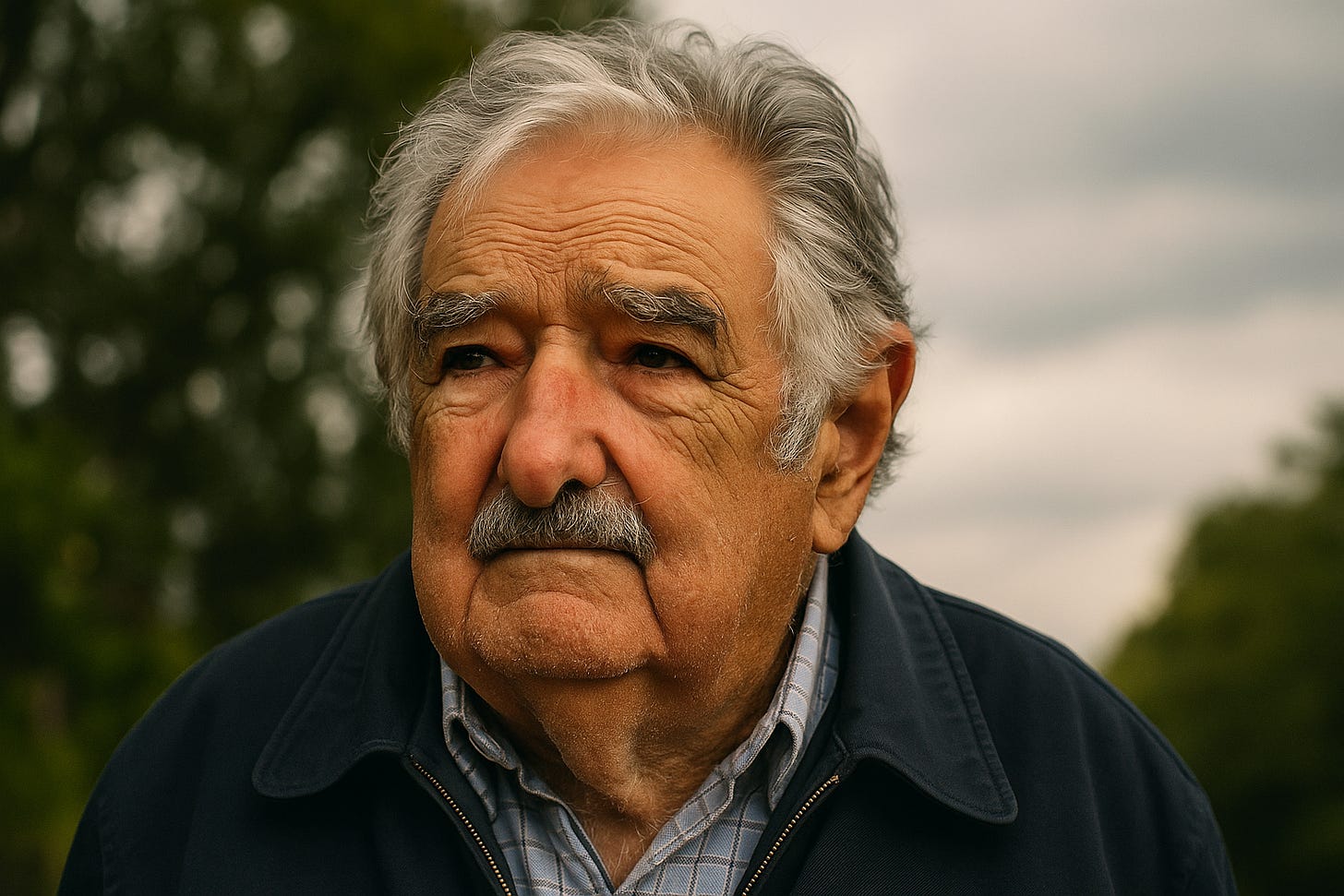

José Mujica: the flawed dignity of a man who lived as he spoke

José “Pepe” Mujica has died, and with him passes one of the rarest figures in modern political life: a man who grew not just in age or office, but in depth. Not all who evolve grow wiser. Mujica did — though not, it must be said, without contradiction.

It is difficult to think of another statesman whose early biography would cause one to recoil more sharply. A self-declared Marxist-Leninist in his youth, Mujica helped lead the Tupamaros, an armed guerrilla group responsible for kidnappings, robberies, and attacks in Uruguay during the 1960s and early ’70s. For these actions, he spent nearly 15 years in prison, many of them in solitary confinement, often under conditions that would have broken most men. That past is not incidental. It shaped him, and not always for the better. Even his later political sobriety cannot be entirely disentangled from the romanticism — and the violence — of that earlier vision.

And yet.

There is something more to be said about a man who began as a revolutionary and ended, in his own words, as a “neo-Stoic.” A man who renounced comfort not for performance, but from conviction. A man who could speak simply because he lived simply — not as affectation, but as principle. He donated 90% of his salary. He drove a battered Volkswagen Beetle. He lived on a small farm with his wife and their animals. He refused to move into the presidential palace. When asked why, he replied, “My wife would throw me out.”

There was humour in him, but not the humour of deflection. It came from a deeper place: the recognition that power is both fragile and absurd. That no man, whatever his title, is exempt from the ordinary tasks of life. And in that recognition lay a form of dignity — not the dignity of prestige, but of coherence.

He criticised excess wherever he saw it — not just among his opponents, but within his own camp. “How hard it is for them to let go of the cake,” he once said of certain left-wing elites who spoke the language of revolution while living in comfort. It was the kind of remark that few leaders make anymore — not because they don't see the hypocrisy, but because too many are too entangled in it.

Mujica, for all his flaws, was not. His consistency lay not in dogma, but in a kind of moral economy. He lived as he believed a man in power should live — not by withdrawing from the world, but by refusing to exploit it. There was, in that refusal, a kind of courage: not the courage of the barricade or the battlefield, but the slower, quieter courage of living as though your values mattered more than your convenience.

I do not write this as an admirer of his politics. I disagreed — and still do — with many of his decisions, sympathies, and alignments. His praise of the Castro regime, his leniency toward the Chavista disaster in Venezuela, his enduring affection for the vocabulary of the old Latin American left — all this I found, and find, unconvincing at best, harmful at worst. He could be wrong — and sometimes dangerously so — about what power meant, about where justice lay, about what kinds of suffering should be named and which ones conveniently ignored.

But disagreement is not incompatibility. And a human being is not reducible to his errors. Mujica was never unthinking. And what marked him, over time, was not obstinacy, but a capacity to reflect, to shift tone, to challenge even those with whom he once stood shoulder to shoulder. He could praise Fidel and criticise him. He could speak up against authoritarianism from the left when conscience demanded it. He did not pretend that loyalty required blindness.

He was, to use a term now almost quaint, a man of character. Which is to say: a man whose actions over time formed a shape. Not a perfect one, not symmetrical, but recognisable — and not in spite of the flaws, but through them. He bore the complexity of his life without the need to simplify it. He admitted mistakes. He learned. And he retained something that many in political life lose entirely: the capacity to think without posing.

He often quoted the Stoics, and though he was not, strictly speaking, a Stoic, he understood something of what they meant. That freedom is not the right to do whatever one pleases, but the discipline to need less. That honour is not the name others give you, but the shape you give your life. That restraint is not weakness, but a form of self-governance.

And perhaps this is the quiet lesson of Mujica’s presidency — and indeed of his life. That politics need not be theatre. That the ethical life is not lived in declarations, but in daily practice. That it is possible, even now, to believe in something without turning belief into branding. That a man can be radical in youth, reflective in age, and consistent in his humanity across both.

It is hard to imagine him in today’s media ecology — where so much depends on outrage, on marketing, on the carefully curated self. Mujica did not curate. He cultivated. He tended to things. To soil, to animals, to his words. He moved slowly. He spoke plainly. He aged honestly.

He died as he lived: quietly, without display, in the same small house, with the same old car in the driveway. His ashes were interred beneath a tree he had planted on his farm, beside the grave of his dog Manuela, who had died years before him. No palace. No grand epilogue. Just the closing of a long and serious life.

Uruguay has declared days of mourning. Leaders from across Latin America have issued tributes. But the man himself would likely have shrugged at the fuss, preferring to return to his vegetables, to his tools, to his garden — the things that asked nothing of him but attention.

We need not agree with the man to honour what he stood for at his best. We need not excuse his past to recognise the moral turn it took. He lived out, however imperfectly, an idea that deserves our attention: that character is not forged in the clarity of youth, but in the difficult years after. That one can grow freer, not more rigid, with age. And that to be true to oneself is not the same as to be indulgent toward oneself.

In a political culture hungry for purity and addicted to judgement, Mujica reminds us that human beings are not theories. They are shaped by context, by error, by memory, by survival. And sometimes, just sometimes, a man emerges from a violent youth not broken, but reconstituted — not as an icon, but as something harder to name and easier to overlook: a human being, trying to live honestly.

That, more than any policy or aphorism, is what deserves to be remembered.

Miklós Cseszneky