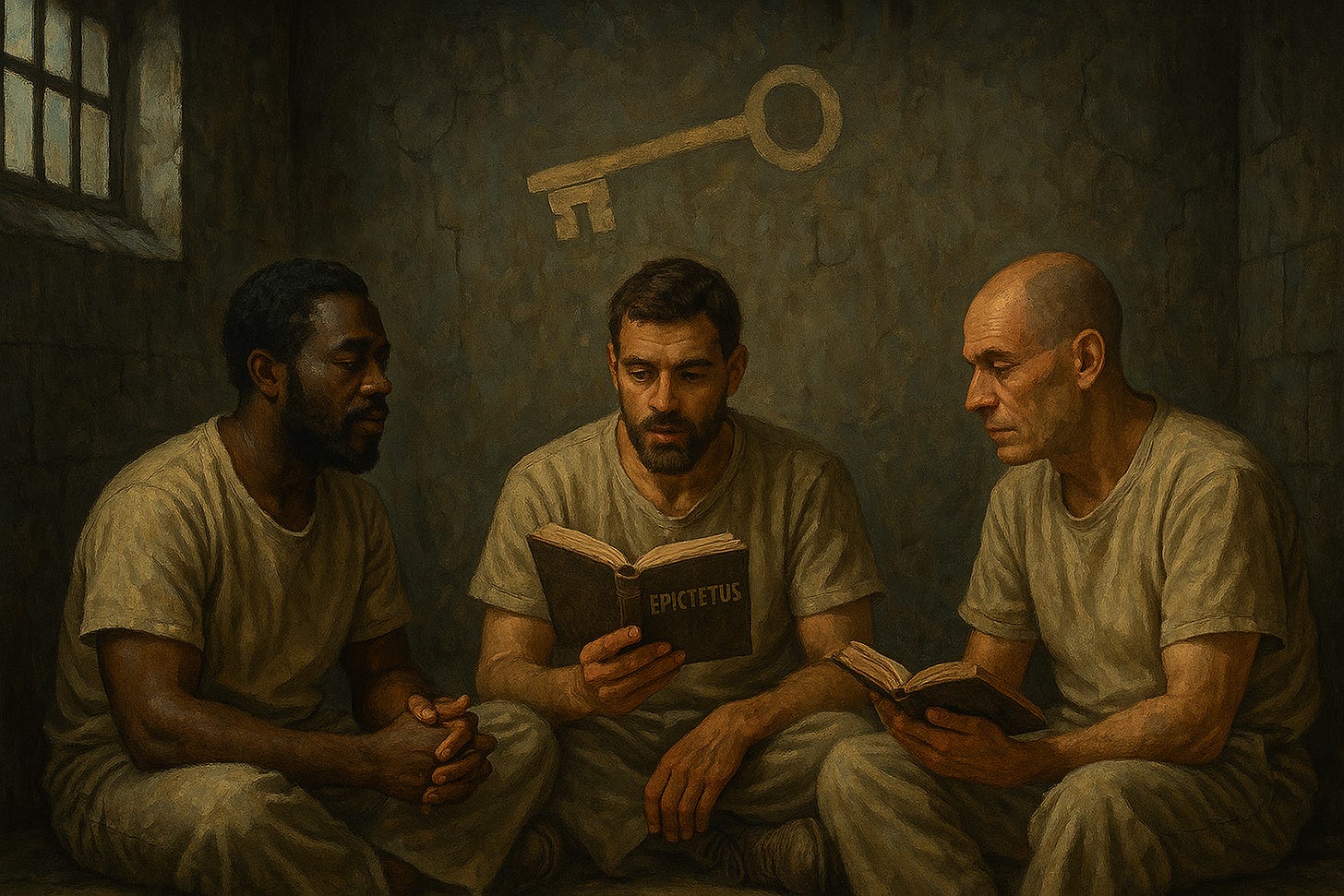

A recent article in the Daily Mail offered an unusual portrait of life inside a British prison. Inmates at HMP Wayland, a men’s facility in Norfolk, have formed a Stoicism discussion group. They meet to read Epictetus, discuss the discipline of desire, and reflect on what can and cannot be controlled. In a setting shaped by violence, hypervigilance, and arbitrary authority, this quiet circle of ancient philosophy stands out—not just as curiosity, but as reminder.

It would be easy to treat this story as a kind of novelty. The contrast is striking: men convicted of violent crimes now quoting Marcus Aurelius. But the deeper one looks, the more this juxtaposition begins to fade. Because prison, in many ways, is the proving ground for any philosophy that takes freedom seriously. Not the freedom to do whatever one wants, but the deeper, inner kind: freedom from compulsion, from rage, from false hope, from the endless attempt to arrange the world just so.

That is precisely what Stoicism offers. And what many of us, though less dramatically confined, still need.

We live behind bars, too. Not of concrete and steel, but of expectation, appetite, grievance, and comparison. Our prisons are lit with screens. Our walls are built from the pursuit of status, the demand for validation, the chronic fear of missing out. We scroll through curated lives, always lacking, always late. We accumulate more than we can enjoy, chase more than we can master, and exhaust ourselves in the maintenance of identities that grow increasingly fragile the more they are affirmed.

The Stoics called these things “indifferents.” Health, wealth, reputation, pleasure. Not evil, not to be despised—but not to be mistaken for the good. They are things that happen to us, or leave us, or tempt us to treat life like a ledger. They are the stuff of almost every marketing campaign and much of our own regret. And the great error, according to the Stoics, is not in enjoying them, but in being owned by them.

Prison, paradoxically, strips much of this away. And in doing so, it can become a site of clarity. What remains when you lose status, control, comfort? What remains when no one is watching? For those willing to face these questions directly, prison can also be a school—of self-mastery, of inner freedom, of learning to distinguish between what can be shaped and what must be borne.

The men at HMP Wayland are not saints. They are not seeking exoneration through philosophy. But in their study of Stoicism, they are confronting the same central truth: that dignity does not require ideal conditions. That even behind locked doors, the mind can be made free. That the person who governs himself is, in a real and ancient sense, never truly imprisoned.

Some of them speak of being provoked and remaining silent. Others of learning how to think before acting, or how to name their emotion before obeying it. These are small victories, but hard-won. In a place where violence often follows mere perception of disrespect, restraint becomes revolutionary.

One inmate described it as “freedom inside the cage.” Another said he found in Epictetus a voice “that actually knew what this was”—not just incarceration, but the degradation of being acted upon, of having one’s identity filtered through guilt, shame, and institutional routine. What these men grasp, intuitively, is that Stoicism is not abstraction. It is a toolkit. It begins with the premise that life is not fair, not kind, and not in our control. And it proceeds from there, asking only: what, then, is up to you?

We forget how radical this idea is.

In the modern moral climate, freedom is almost entirely outward: freedom to speak, to move, to express, to claim. But inward freedom—the freedom not to be mastered by fear, or anger, or impulse—this we rarely discuss. It is quieter. Less visible. And yet without it, the rest is fragile.

There is something deeply countercultural in the Stoic refusal to dramatise suffering. To grieve, yes, but not to collapse. To acknowledge injustice, but not to become its echo. To live in reduced circumstances without reducing oneself. This is not passivity. It is a kind of moral anchoring. The Stoics do not teach us how to win. They teach us how to remain intact.

And this is why the story of a prison Stoicism group matters. Because it reminds us that philosophy is not decoration. It is not leisure for the educated or indulgence for the idle. It is a discipline—a moral exercise, a daily rehearsal of clarity. In a culture addicted to affirmation, it is an ethic of restraint. In a world built on appetite, it is a practice of distinguishing what we want from what we are.

Most of us will never live behind bars. But we will know confinement. The loss of freedom through illness, aging, failure, disappointment, betrayal. The loss of imagined futures. The abrupt end of what we thought we were owed. In those moments, the slogans of modern life fall strangely flat. What we need then is not permission to feel more, but the tools to remain whole.

And the tools, it turns out, are old. Older than democracy. Older than therapy. Older than most of what we confuse with progress.

When Epictetus, a former slave, told his students that “no man is free who is not master of himself,” he spoke not in metaphor but from memory. The bars he escaped were real. But so too was the inner fortress he built—brick by brick, thought by thought. And what he passed down was not an argument but a method: attention, judgment, detachment, choice.

None of this makes Stoicism easy. It is not soothing. It does not offer closure or release. It asks us to live on a narrower path. To rehearse death. To renounce indignation. To be suspicious of ease. But it also offers something rarer than comfort: lucidity. And the kind of dignity that cannot be given by others, and therefore cannot be taken away.

There is something sobering—and moving—about these men in HMP Wayland sitting with Marcus Aurelius. They are not debating abstractions, but practising mental posture. They are not free to come and go, but they are learning to come and go within themselves. They are recovering what the rest of us, in our performative freedom, too often forget: that a person is not the sum of his circumstances. He is the shape of what he does with them.

In some sense, prison is a compressed world: an intensified version of the hierarchies, injustices, and vanities that mark ordinary life. And there is one result, quietly reported but worth amplifying: since the Stoicism programme began at HMP Wayland, rates of violence have significantly declined. The prison, once marred by eruptions of aggression and retaliatory harm, has grown calmer—not due to increased force, but to increased self-awareness. This is not the product of doctrinal instruction. It is the fruit of inner work. When men learn to name their anger, they may not need to act it. When they grasp the idea that insult is not injury, they may discover space to pause. What has been cultivated is not ideology, but interiority—a self capable of stepping back from its own impulses. It is this compression that makes the Stoic response all the more vivid. And perhaps instructive. We do not need walls to live as if we were constrained. We often submit to compulsions, anxieties, and social pressures that narrow the soul more effectively than bars. We believe ourselves to be free simply because we are not confined. But internal liberty is something else entirely.

Freedom, as the Stoics understood it, is less a condition than a competence. It is the ability to respond, rather than react. To suffer without resentment. To act without demand. And in a society increasingly driven by spectacle, outrage, and performance, the quiet dignity of that capacity may be more valuable than ever.

We are all, in some way, practicing how to be free. The question is only whether we know it.

Miklós Cseszneky