Against Noise

On the Moral Cost of Constant Distraction

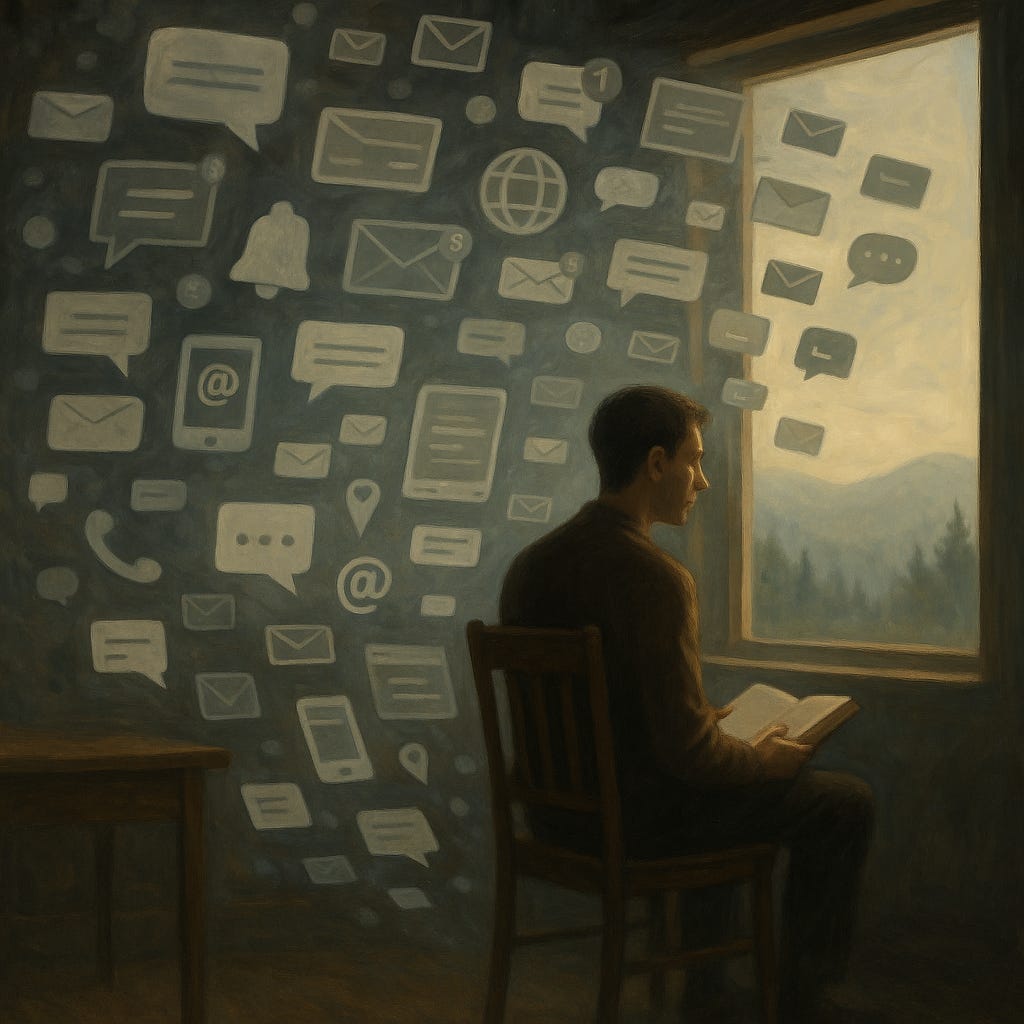

There is a kind of noise that has nothing to do with sound. It does not shriek or blare; it doesn’t arrive through the ear at all. It settles in the mind — through screens, updates, alerts, insinuations. It is the noise of the world pressing too closely in, the ambient clamour of everything asking for our attention at once. The world no longer shouts; it whispers constantly. And in this, there is no rest.

This kind of noise is hard to name because it is so familiar. It travels with us — in our pockets, on our wrists, across our screens. It pours in through emails, pings, chats, pop-ups. Even the things meant to enrich us — a documentary, a well-written article, a podcast on ancient philosophy — arrive alongside a hundred other invitations to click away. We live, increasingly, in an environment structured for interruption. Even solitude is rarely spared. The room may be silent, but the noise continues: in the urge to check, to refresh, to respond. And then, perhaps worst of all, in the hum of inner agitation that follows.

We speak of it lightly, as if it were an inconvenience or a side effect of modern life. But I’ve come to think it is something graver. Noise, in this broader sense, is not just a nuisance to the thinking mind. It is a moral condition. Or rather, it creates the conditions in which moral life becomes harder to sustain.

What gets drowned out in noise is not merely silence, but depth. Depth of attention, of thought, of character. When everything is interruption, nothing is truly entered. We become strangers to patience — and strangers, perhaps, to ourselves.

There is something oddly intimate about attention. We offer it not just with the mind, but with the will. It’s how we give ourselves — slowly, deliberately — to people, to ideas, to the world as it is rather than as we wish it were. In this sense, attention is a kind of ethical posture: an orientation of care. When we attend to something, we permit it to matter. And in doing so, we allow it to shape us.

But noise erodes this. It fragments thought before it can deepen. It scatters intention before it can form. A man in a state of chronic distraction is not simply busy; he is prevented, over and over, from the work of perception. And this has consequences. Not just in productivity, as the modern vocabulary would have it, but in the texture of one’s life. What is never fully noticed is never fully known. And what is never known cannot be rightly judged, loved, or mourned.

There is a quiet violence in this. Not the sort that draws headlines, but the kind that gradually hollows out interiority. One begins to confuse stimulation with meaning, responsiveness with wisdom. The mind, once capable of slow discernment, becomes trained instead to react. And so much of what is human — contemplation, nuance, subtlety — starts to appear inconvenient, even suspect.

It becomes harder, too, to be alone without feeling vacant. Streaming services ensure that silence never has to fall. Messaging apps ensure one need not sit in unconfirmed thought. The whole structure of our digital life — and it is a life, not merely a tool — is designed to make uninterrupted time feel strange, even irresponsible. The man who closes his laptop and lets himself be bored risks guilt. Shouldn’t he be reading something? Watching something? Answering someone?

And so noise persists even when the devices are off. It loops inside the head — half-finished messages, unfinished tasks, remembered images, uninvited comparisons. The internet has not only extended the social world; it has internalised it. One is no longer alone even in one’s own mind. Others have taken up residence there — not as guests, but as ghosts.

In this sense, noise is not merely a product of the age, but its solvent. It dissolves the distinction between the urgent and the important. It prizes the instant over the lasting, the performative over the true. And it offers, in return, a kind of relief — the relief of never quite having to face things. To live in noise is to be continually preoccupied, which means never truly responsible. There is always another notification to blame, another context-switch to explain one's evasion of depth.

It is tempting, in this light, to retreat. To imagine the solution lies in silence alone: a cabin, a switch-off, a well-curated minimalism. But withdrawal is not the same as freedom. And silence, too, can be evasive if it merely serves the self. The deeper discipline — the more difficult one — is to stay in the world while refusing to be absorbed by its noise. To remain attentive, which is to say, present and porous, in an age that rewards the opposite.

This form of resistance is not glamorous. It does not lend itself to photographs or declarations. It involves things like reading slowly, writing with care, listening when no one is watching. It is built from habits so small they seem invisible — until, one day, they are the only things that hold a man together. And it requires the humility to begin again, often, after distraction has scattered him once more.

To live against noise is not to become austere or aloof. It is to become available — to truth, to beauty, to sorrow, to complexity. It is to reclaim one’s inner landscape from the constant colonisation of urgency. And it is, I think, a kind of fidelity: to the world as it really is, and to the self as it is still becoming.

What we need, then, is not silence as escape, but silence as soil. Not withdrawal, but rooting. The kind of quiet in which speech regains meaning, action regains proportion, and attention regains its dignity. We may not control the noise that surrounds us, but we can learn not to echo it. And perhaps that is where the ethical life now begins: not in saying something new, but in hearing again what we’ve forgotten how to notice.

Miklós Cseszneky